Bad Grades? Dumb Down the Grading System

It was only a matter of time. As the National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) scores continued to tumble despite the dumbing down of the tests themselves — they now measure social-emotional characteristics in addition to academics — public-school administrators had to do something. The solution, at least in California and reportedly soon if not already in other states, is to lower the grading scale.

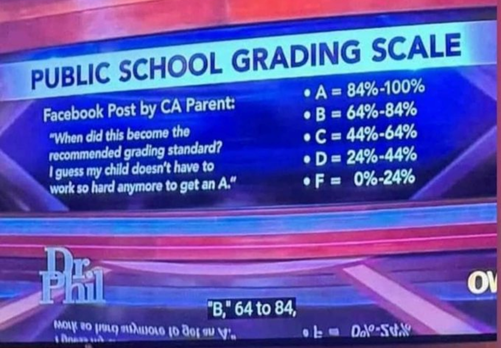

In April, reports surfaced of a dumbed-down California grading system (shown below), which was purportedly posted on Facebook by a concerned California parent and brought to light nationally on the Dr. Phil TV show. The chart turned up on X, courtesy of a user called “Joker King,” who wrote: “84-100 is an A? 24-44 is a D? In my day, anything below 65 was failing, now it’s a C. This is unacceptable....”

The grading scale was decried by nearly all who commented on the post. One responder uploaded a Peanuts cartoon with the caption: “No one is going to give you the education you need to overthrow them.” Another wrote: “My New York school is about to implement the same thing but less obvious, so therefore more insidious. It’s called ‘equity in grading.’ We will just eliminate 0-50 and all grades [will] start at 50. If a kid can make it to 65, they pass.” Yet another user recalled: “When I was in school you had to have a 70 to pass.”

Although the hour-long daytime Dr. Phil show on CBS ended in the spring of 2023 and, according to the official Dr. Phil website is now streaming on Merit+, independent sources, including Snopes, determined that the screen shot of the grading system had in fact appeared on the show. While Snopes claimed it could not verify the authenticity of the grading scale, neither could it be disproved.

But the move to lower grading standards has been in the works since the pandemic. In November 2021, the Los Angeles Times published an article describing how, “faced with soaring Ds and Fs, schools are ditching the old way of grading.” The article described the tactics of Alhambra high-school teacher Joshua Moreno, who “got fed up with his grading system,” which he derided as “a points game” and “inequitable.”

Moreno scrapped the grading system, stopped assigning homework and awarding points for students’ work, and instead began giving them “multiple opportunities to improve essays and classwork.” His goal was “to base grades on what students are learning, and remove behavior, deadlines, and how much work they do from the equation.” For many parents, this was a how-to for dumbing down their children’s education.

According to the Times, Moreno was hardly the only teacher or school district to embrace such practices:

- Los Angeles and San Diego Unified — the state’s two largest school districts, with some 660,000 students combined — have recently directed teachers to base academic grades on whether students have learned what was expected of them during a course — and not penalize them for behavior, work habits, and missed deadlines. The policies encourage teachers to give students opportunities to revise essays or retake tests to show that they have met learning goals, rather than enforcing hard deadlines.

School district leaders excused the obvious downgrading of classroom practices as “teaching students that failure is a part of learning.” In letters addressed to principals, they asserted that traditional grading “has often been used to ‘justify and to provide unequal educational opportunities based on a student’s race or class.’” The letters alleged that “century-old grading practices” perpetuate achievement gaps by “rewarding our most privileged students and punishing those who are not.” In other words, students in most need of traditional education will again be shortchanged, as the so-called “privileged students” will find a way to succeed, perhaps through tutors or other outside means provided by their “privileged” parents.

‘Equity Grading’

In the realm of equity in grading or “equity grading,” the name Joe Feldman frequently appears. Feldman is a former teacher, administrator, and self-appointed “grading consultant” who wrote the book Grading for Equity.

The book is promoted as emphasizing “accurate, bias-resistant, and motivational grading practices that improve learning, reduce failure rates, and strengthen student relationships.” It supplies a historical backdrop that implicates traditional grading as “a sorting mechanism to provide or deny opportunity, control students, and endorse a ‘fixed mindset’ about students’ academic potential,” clearly indicating the biased premise upon which the content is based.

One teacher who reviewed the book took issue with a number of its precepts, including the recommendation that teachers should accept “late work” from students as a matter of course, and the assumption that “all my ‘grades’ are on summative assessments only...that I don’t recognize growth...and that every assessment assesses the same skills (and therefore a student’s understanding of those skills changing from task to task).”

This teacher credited the book as a “conversation starter among staff,” but found its argument “poorly supported” and “the warrants underlying the argument profoundly flawed ‘if you want a practicing teacher to drink the Kool-Aid.’”

Fordham Institute findings

In February of this year, the Fordham Institute published a policy brief titled Think Again: Does ‘equitable’ grading benefit students? The report shows that changes in grading practices promoted by equity grading, such as preventing teachers from giving less than 50 percent credit to students regardless of how little work they do or how poorly they perform, bans on grading homework or class participation, etc., “ultimately harm the students they are meant to help.”

For many parents, Fordham’s findings are obvious. Lowering standards through lenient grading systems and prohibiting penalties for late assignments and cheating only serve to discourage responsibility and accountability among students, while hampering teachers’ efforts to manage their classrooms. High expectations create motivation; low expectations encourage laxity.

Even the Washington Post wrote of the Fordham report: “The researchers admit that some adjustments in traditional grading can be useful. ‘But top-down policies that make grading more lenient are not the answer, especially as schools grapple with the academic and behavioral challenges of the postpandemic era.’”

The report notes that many of the equity-based grading reforms were “not birthed during Covid,” although the push to implement them emerged from the pandemic’s disruption and chaos. But as the report authors write, the increasing popularity of these reforms and their growing implementation by states and districts is new. “Unfortunately, many of these policies lower academic standards and are likely to do long-term damage to the educational equity their advocates purport to advance.”

Grade inflation

Another factor in the equitable grading debate is grade inflation, by which “teachers assign ever higher grades for the same level of academic work.” The Fordham report contends that “in the last few years, grade inflation has not only accelerated but has become normalized and pervasive, reframed as a core battleground in the struggle for greater educational equity.”

The report references the influence of the previously mentioned Joe Feldman, whom the authors note “regularly consults with school districts and whose 2018 book Grading for Equity has become a staple of teacher professional development.” The authors question Feldman’s contention that his grading reforms actually counteract grade inflation, “particularly for more privileged students,” because “equitable grading no longer includes nonacademic, compliance-related, and subjectively interpreted behaviors.” Feldman worries, for example, that “classroom participation” — which he considers to be a subjective grading practice — “will disproportionately inflate the grades of privileged students—who often benefit from advantages such as being more likely to encounter academic English at home.”

Fordham refutes this concern, writing:

- Although this may be true in some cases, the claim that his recommended policies combat grade inflation ultimately confuses two aspects of grading: what should contribute to a course grade and how those activities should be assessed. After all, a teacher might grade class participation (the “what”), which Feldman claims may lead to grade inflation, but also use a rubric to do so strictly and fairly (the “how”).

The report further finds that, contrary to claims that “strict grading harms students,” lenient grading actually does so by leading to “less learning.”

The Fordham report is packed with information and data without discounting everything about equity grading. But even when the authors concede that some classroom biases exist, they maintain that these “are not just about outright prejudice.” They believe reforms that “increase transparency around expectations and grading can be beneficial, noting: Research confirms that scoring rubrics can reduce the effects of bias.”

Reading is key

Supporters of traditional education know that the ability to read is key to acquiring all other knowledge, including math, and that children in general are not being taught to read, hence the push to lower the grading scale.

A May 2023 editorial in the Los Angeles Times admitted that California “knows how to turn students into better readers,” and questioned why this wasn’t happening. The editorial bemoaned the fact that “more than half of California students can’t read at grade level,” and acknowledged that despite a degree of normalcy having been restored post pandemic, test scores from the spring of 2023 showed that “the percentage of grade-level readers crept down ever so slightly, from 47.5 percent to 46.7 percent.”

The editorial stated: “Learning to read is a complex process that requires phonics and related skills, with students directed by a teacher through the decoding of letters into sounds, sounds into words, words into sentences and stories. But it also requires building children’s vocabularies as well as their enthusiasm for literature.”

Phyllis Schlafly could have explained all this many years ago when she was teaching her own children to read using the phonics method. While the article touted the “science of reading,” as if it were a new phenomenon, this method is little more than the proven phonics instruction that Phyllis and others touted for decades as the most effective way to teach reading. (See Education Reporter, December 2023.) The Times reported that as of July 2023 some 32 states, New York City, and Washington DC “had adopted policies favoring science of reading, according to an analysis by Education Week.” The editorial acknowledged that “bringing phonics out of the shadows won’t magically turn students into top-notch readers. But it can definitely bring about large-scale improvement and should be the state’s highest educational priority over the next few years.” Whether or not that happens remains to be seen.

Ulterior motives

In March of this year, For Kids and Country founder Rebecca Friedrichs and longtime newspaper editor Roger Ruvolo, authored a piece in the Washington Examiner that suggests public schools “are intentionally” dumbing down education. “This casts a pall on the country’s future, and this ominous cloud is cast by design,” they wrote.

As she explained in her 2018 book Standing Up to Goliath, Friedrichs laid much of the blame for the state of America’s public schools at the feet of the teachers’ unions, particularly in the states where the unions wield the most power. She and Ruvolo used Illinois as an example. “Nothing but goose eggs in reading at 32 Illinois schools, according to a 2022 report from the Illinois State Board of Education,” the authors wrote.

As she explained in her 2018 book Standing Up to Goliath, Friedrichs laid much of the blame for the state of America’s public schools at the feet of the teachers’ unions, particularly in the states where the unions wield the most power. She and Ruvolo used Illinois as an example. “Nothing but goose eggs in reading at 32 Illinois schools, according to a 2022 report from the Illinois State Board of Education,” the authors wrote.

They added that despite Illinois school districts spending more than $30,000, $40,000, or even $50,000 annually per pupil, “not a single student — zero — tested at grade level in reading in 32 schools. Similarly, not a single student tested proficient in math in 67 Illinois schools.”

The authors charged that, for decades, teachers unions “have worked relentlessly to convince Americans that we need trillions poured into our schools. They’ve used our tax dollars to destroy our children: to indoctrinate them, sexualize them, turn them against parents, demoralize them, dumb them down, and replace learning fundamentals with communist propaganda.”

But parents should take heart. When news outlets like the Los Angeles Times and the Washington Post acknowledge that all’s not well with public education, it’s a step in the right direction. There’s also hope in the increasing push for school choice, the rise in homeschooling and private schooling, and the burgeoning number of other educational alternatives such as microschools.

And all is not lost when concerned parents like Moms for Liberty, Moms for America, and many other courageous parents groups, take center stage and demand change.

Want to be notified of new

Education Reporter content?

Your information will NOT be sold or shared and will ONLY be used to notify you of new content.

Click Here

Return to Home Page